|

The Potala Palace in Lhasa a masterpiece of sacred architecture, a defensive fortress, and the residence of the Dalai Lama. The palace is looked up to as the symbol of the country and an illustration of the religious struggle for purification. Ancient and unexpected influences relate this sacred symbolism in stone to the rest of the world, with a classic architectural language fundamental to any political and social society.

Values in design |

|

|

Values

The Tibetan stupa was borrowed from India’s Buddhism and served 3 functions: Give divine political power, reliquary of holy elite, and reliquary of the overall temple. The mandala is the starting point of the stupa, a circular “container of essence” or “wholeness of self.” “It was built upon the center of two intersecting lines, which were at right angles. The intersection of these two lines came to symbolize the confines of a diety.” a As a dwelling place of the gods, temple symbolism pushed the Potala palace upward to the heavens. “The vertical axis, enhanced by the skylight rising like a turret on the summit of the temple, symbolizes the union of the earth and the sky. Therefore, the dwelling of the divinity is at the core of the cosmic mountain, in the luminous centre of these architectural mandalas.” b |

(sosoliu – flickr/creative commons license) |

The stupa is arranged from a diamond-shaped mandala, with 5 sides representing the 5 dhyami buddhas, the 5 directions in space, 5 bodily sense, 5 bodily organs, or 5 enlightenments. The 13 concentric rings upward symbolize the 13 stages of advancement. The glittering gold top represents unification of the sun and moon, wisdom and compassion bringing enlightenment.

The site’s origins as the cave home of Tibet’s first emperor, Songstan Gampo, likely inspired its later use as the royal burial place. This sacred cave is now an 89 ft² hall Chogyal Drubphuk and has an entrance plate that reads “Profound fruits in fields of fortune.” This title suggests the formless heavenly rewards that await the deceased because of their good works in this life.

- Spiritual progression for the people

| Such was a procession undertaken by the laypeople as they daily gazed up at the tall towers, flashy red palace, the sunlight temples, golden stupas, and lush courtyards. The visualization of their ideal gave them a collective hope.

Those privileged to entire the palace entered a world of color and splendor. Sunlight shone through the apertures onto splendid frescoes and streamers, gilded beams and architecture, dazzling with a glimpse of paradise. The maze-like layout of the lower city created an atmosphere where one would desire open light space. “The designers made use of the spatial array to create many complicated narrow chambers, where the shaking light of the butter lamps illuminates dark corners, and shafts of sunlight filtering down from high windows pick out the slow dance of particles of ancient dust in the deep corridors.” c |

| Is it coincidence that the layout and front view of the Potala palace looks a lot like the flag of Tibet? Snow lions on the flag represent secular and religious rule. They raise up the red flaming symbol of truth, virtue, and Buddha toward the holy sun. Blue and red stripes radiate out from the golden sun at the peak of a pyramid. The palace likewise rises up a white pyramid to elevate the red temple below a golden roof. The twelve stripes represent the twelve tribes that are believed to be Tibet’s origins. |  |

The place all this occurs is the Potala palace, the secular and religious center of Tibet. It is the dwelling site of Tibet’s founder, Songtsan Gampo. He built the first palace in 637 to greet the arrival of his wife Wen-Che’eng, a marriage through which he solidified an alliance with China’s Tang Dynasty. It has come to represent the secular and religious rule of the country, also containing symbols of truth, virtue, and Buddhism.

The architectural legacy of ancient pyramids and ziggurats suggests a coming together of sensibilities from around the world, from east Asia to Europe, which has been noticed in many Tibetan sites. The greatest influence was India’s Buddhism, and architecture unique to early India can still be widely seen in Tibet. Tibet was isolated from India for many years, starting in the 12th century, and never received India’s later evolved Buddhist style, instead evolving on its own.

|

The Potala palace was the scene of massive protests after Communist China invaded in 1950 with an army of 84,000. An estimated 1 million people have been killed from Chinese suppression since Tibet’s government officials were exiled in 1959. The treasures of Potala were looted and priceless historical records lost. But even though 6,000 monasteries were destroyed by the Mao’s ‘cultural revolution’, the Potala palace was preserved.

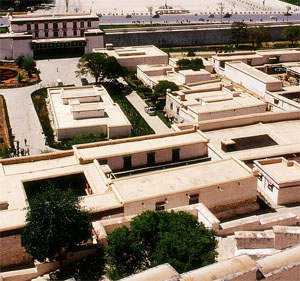

A $6.4 million restoration by China in 1990 destroyed much of Potala. Most of the lower governmental buildings were torn down. The communists built a large front square that looked like that in Tiananmen, with suppressive security, like that at Tiananmen. This square is “unattractive and totally uncomplimentary to the historic grandeur of the Palace, sort of like Corbusier’s city planning of Paris.” d |

(Party0– flickr/creative commons license) |

- Blend in with the landscape

The most noticeable feature of the Potala Palace is how the walls blend seamlessly with the cliffs. The cliffs appear to actually be part of the building’s massive foundations. The structure utilizes natural slopes and features to blend in with the environment.

“Details of the craggy truncated pyramid are swamped in the hugeness of its impassible walls, with their stairways that seem to reproduce the zig-zag patterns of mountain ledges.” e

No nails were used in construction. Rammed earth and simple stone walls were reinforced with copper, but largely appear natural. “Simple equipment was used to fashion this skyscraper- an achievement on a par with the building of the pyramids.” f The same geomorphic principles of construction are seen throughout the Middle East.

The Potala Palace also fit in with Tibet’s traditional Himalayan architecture. The overall shape of the original Tibetan nomad tent is seen in the complex of structures, with the hip and gable roof and four sided towers.

|

Fabric was frequently used in Tibetan homes to insulate warmth from the cold, and this was transferred in the palace to great tapestries that hung throughout the spaces. The tapestries were integrated into the form and function of these spaces. Clothing worn by the occupants further integrated them into the architecture and functions of the spaces, in a way similar to the Hebrew temples.

The white cloth used for windows in traditional homes became the white shaded windows seen in the palace today, with black window frames that emphasize the importance of the aperture. These windows taper slightly inward and are topped with a dentaled roof, imitating the overall look of the building. |

(preston.rhea – flickr/creative commons license) |

The white window thus symbolizes the thin veil that separates the space in the building and the heavenly realm outside of the palace.

- Dynamic use of space

| The Buddhist adherence to the belief in impermanence is the reason why all artists and architects are anonymous. All individuality is given up in the struggle for purification and enlightenment. Asceticism demanded spaces that are devoted to heavenly pursuits and deny human needs. Lack of plumbing, for example, meant that all water, waste, and daily needs were carried up and down the steep cliffs.

Few of the large gatherings were held inside buildings, but in the spacious courtyards, such as ritual dancing and pilgrimages. Lhasa has little precipitation, which allows for flat roofs and frequent outdoor activities. |

(melanie_ko– flickr/creative commons license) |

| Indoor spaces used furniture and removable decoration to keep a nature of space far from permanent. Prayer flags were raised with written prayers that transferred their devotion to heaven as they flapped in the wind. Large banners tanka sanctified spaces for certain uses and could easily at any time be scrolled up and moved. These were frequently juxtaposed with detached metal sculptures, such as the statue of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara in the Dalai Lama’s private chapel.

This decoration has been compared to a drive-in movie, a temporary portrayal of real and abstract concepts that can quickly be changed to something else. Sensory appeal in sound, texture, smell, and sight took a role in the very architecture. Each detail related the foundational values of the architecture to the occupant’s perceptions, impressing a deep religious principle. For example, in the wall decoration, “the opali may also suggest a stalactite curtain, allowing us to speculate on the temple conceived as an architectural replica of the world structure, with the entrances opening like caves in a magic mountain.” f |

(Nao Iizuka– flickr/creative commons license) |

- Home to the political stronghold

The palace also served as a home to the Dalai Lama and Tibet’s political leadership. For many years they were born, grew up, and lived in these rooms. Gampo’s original hilltop campus included 1,000 houses. Today, the palace includes thousands of rooms, including residences, entertainment venues, offices, schools, and meeting halls.

The scarlet color of the red palace kept the temperature comfortable, absorbing heat in the winter and expelling heat in the summer. The stone and masonry serves as a thermal mass to likewise cool spaces off in the summer and mitigate the extreme heat differences between nighttime and daytime.

| The walls could be very thick, 16 ft at some places. This not only helped defensively against attacks, but the thin and deep windows blocked out the summer sun and let in the lower winter sun. Most windows face south, just the ideal direction to capture the winter warmth and avoid excess solar gain in the summer.

The supremacy of the government scepter was established by the integration of a palace, castle, monasteries, stupas, and gardens. Just as the buildings retain the character of the original nomad tent, the traditional Himalayan house is constructed in much the same way. White Tibetan homes terrace up hillsides. They are also rectangular, built of massive and imposing stacked stone walls that taper up, a solid foundation of rock, and with a flat roof. Civil war and political intrigue plagued Tibet much of its existence, from the earliest days to today. The reign of the Dalai Lamas was no different. There is speculation that the 9th through 12th Dalai Lamas may have been assassinated early in their lives due to political struggles in the theocentric leadership. |

(melanie_ko– flickr/creative commons license) |

Timeline

| 100 BC | Drigum Tsenpo seeks dominance of the Zhangzhung people |

| 617 | Songtsan Gampo unites Tibet. Marries princess of Nepal and niece of Chinese emperor Taizong. |

| 649 | 1st palace built Kukhar Portrang, ravaged by Chinese invaders |

| 800 | Tibet loses most of central Asia and the imperial government collapses |

| 1578 | Altan Khan of the ruling Mongles names Sonam Gyatso as the first Dalai Lama |

| 1653 | 5th Dalai Lama Lobsang Gyatso (1617-1682) completes Red Palace at Potala Palace |

| 1694 | Red Palace at Potala Palace completed 14 years after 5th Dalai Lama’s death |

| 1922 | 13th Dalai Lama renovates Potala Palace |

| 1950 | China invades Tibet |

| 1959 | Dalai Lama flees Potala Palace to India |

| 1990 | China renovates Potala Palace |

| 2008 | China places heavy restrictions after anti-occupation protests |

Site: Holy Hill and Cave

At 12,000 ft above sea level, Rtse Potala is the highest palace in the world. Potala derives from the Sanskrit word Putuo. The hill it stands on, Red Hill Marpo Ri, meaning “second Putuo hill.” This is the place where Guanyin, the Bodhis attva of infinite compassion and mercy, resided and meditated, located between the earth and the sea, or perhaps in this case between earth and sky. It is considered a sacred hill, a residence of the gods. The founder of Tibet, Songtsan Gampo, also meditated here in a cave. The site is therefore at the same time sacred as a terrestrial hilltop and a subterranean cavern.

In addition to being chosen because of the sacred cave of, Red Hill is an ideal location for a castle, with sweeping views of the entire valley basin and its proximity to trade routes and the Lhasa River.

High buildings on hills were especially popular in Middle Eastern regions as they implied supremacy. Social law dictated that the Dalai Lama be elevated above everyone else. Towers are necessary in any town so that invaders can be seen from afar, from all sides, and so that the local government can keep an eye on the people.

Structure History

The structure of the palace has a simple post and lintel design, with columned halls and walls of piled rocks. Without arches or advanced structural beams, the columns must be close together, reminiscent of the hypostyle halls in ancient Greek and Egyptian temples. The thick walls slope inward and are reinforced by buttresses.

“Technologically, the Tibetans did not progress beyond the basic concept of piling up stone walls so that the bottom of the wall is wider and thicker and can support the weight of what is built on top. The walls of Tibetan buildings slope inward. All early architecture, from the pyramids of Egypt to the ziggurats of the Middle East, uses this basic principle.” h

The original palace had four walls and four gates each, a perfect square, 1,500 ft long and a thousand houses inside. Today, the width to length ratio is almost perfectly 3:4.

| White Palace – Portrang Karpo was completed in 1653 by the 5th Dalai Lama and later expanded by the 13th Dalai Lama. It included a string of buildings on the sheer cliffs. As the palace became the royal residence, accommodations for the Dalai Lama and government were made in the White Palace.

The front courtyard Deyang Shar is spacious with 5,000 ft² of area, dominantly colored yellow. Operas and other performances were held here. The small yellow building in the courtyard is a storage facility for festive banners. The wing to the east served as the private cloister of the Dalai Lama and 150 monks of the Namgyal monastery. The western wing contained governmental offices, a school, national assembly meeting halls, and an eastern courtyard for gatherings. |

(joaquinuy– flickr/creative commons license) |

The white palace has eastern and western “sunlight halls.” The Eastern hall Conqenxag had the most important royal ceremonies.

|

Red Palace – Portrang Marpo The Tibetan government used 7,000 workers from Han, Manchu, and Nepal regions to construct the Red Palace 14 years after the death of the 5th Dalai Lama in 1694. The four central halls are dedicated to the 5th Dalai Lama, with great murals, fabric, and columns. The Western Hall Sixipuncog has an area of 608m² and a plaque that reads “Origin of flourishing lotus” above the “fearless lion” throne.

A chapel North of these halls contains an ancient statue shrine to Avalokiteshvara, with a narrow passage leading down to the sacred Dharma cave. |

(Mot the barber– flickr/creative commons license) |

The Red Palace is five floors high, with two of the floors added in the renovation in 1922. It has a complicated layout, with 4 meditation halls, 35 chapels, shrines, assembly halls, and gold stupa tombs to the 5th and 7th-13th Dalai Lamas, the largest 22m tall. There are vast repositories of libraries for ancient religious texts, armor, weapons, and treasure. The many memorial halls to Tibet’s leaders are bellshaped and have fish and monsters at the roof corners.

Lower Levels – The labyrinth of lower governmental offices and monasteries have mostly been torn down by communist China. Tibet’s army headquarters were once at the bottom of the hill, called in Tibetan “snow”.

Behind the Potala Palace, on the other side of the hill, is Dragon King Pool Zongjolukang, a quiet place for peaceful reflection.

Comparisons to Other Buildings

Nalanda

| A major influence on Potala’s design was Nalanda, India’s ancient center of higher learning, which was based on ancient ziggurats of many years before. Xuan Zang’s description of the site inspired Tibetan builders, with “richly adorned towers”, “precious terraces spread like stars”, “the rafters adorned with paintings”, and “the coloured eaves, the richly adorned balaustrades, and the roofs covered with tiles that reflect the light in a thousand shades.” i

The Buddhist concept of paradise was architecturally illustrated, as “the beams were painted with all colours of the rainbow and were carved and ornamented, while the pillars were red and green.” i |

(Prince Roy– flickr/creative commons license) |

Procession of Site

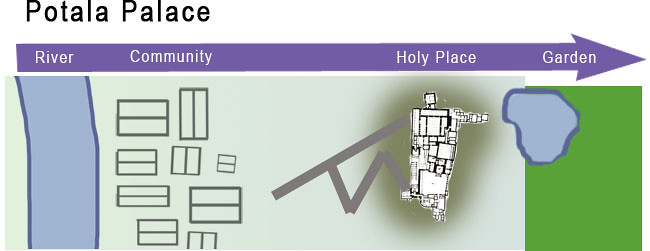

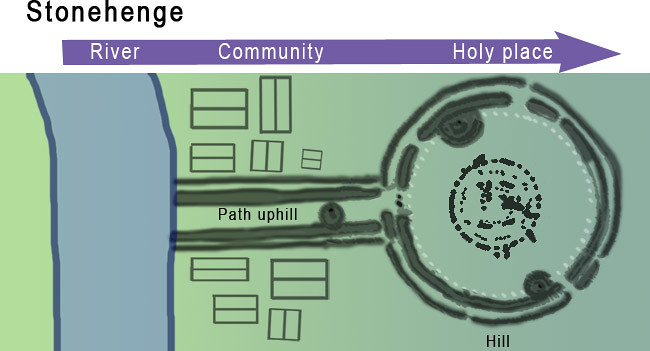

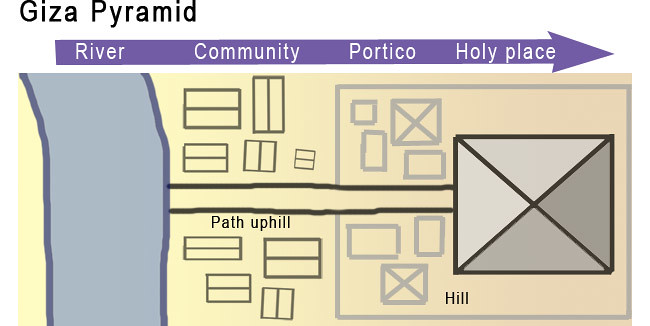

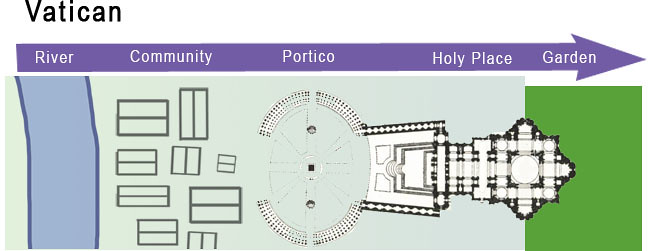

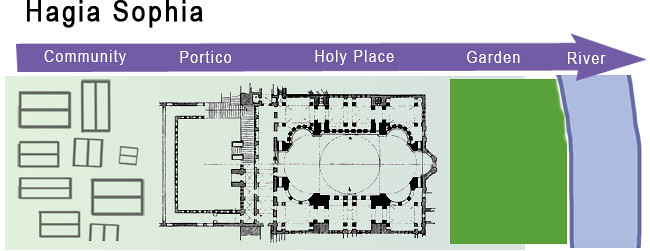

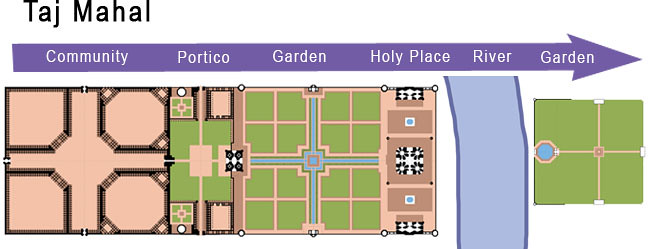

There is a similarity of processional designs in ancient sites. The visitor typically begins at a river, which represents the chaos of first creation. They proceed uphill on a strait causeway or path through a community of homes, civic buildings, or religious buildings related to the site. This town transitions to a temple as the visitor enters a portico, in the case of the Potala Palace a steep climb up a cliff face. Behind the temple is a garden retreat, which represents the paradise of the afterlife or achievement of spiritual exaltation.

Despite what little we know about Stonehenge, the similarity of procession can be seen. Trenches were dug to suggest a mound for the Stonehenge holy site and barrow mounds served as lavish burial tombs for important people.

The great pyramids in Giza’s necropolis had a very similar layout, and similarly served as golden-peaked burial mounds for the nation’s leaders. The Vatican has also follows this same layout, with a garden of rest behind the St. Peter’s cathedral. With over 100,000 ancient paintings and 200,000 statues filling thousands of rooms of a religious and government center, the Potala Palace’s similarity to the Vatican complex is unmistakable.

The Hagia Sophia cathedral changes it up a little, with the river as the ending point, instead of the starting point.

The Taj Mahal is yet more different. A community bazaar transitions through a portico into a garden of man-made rivers. The natural river sits behind the burial site and a final garden of rest behind that.

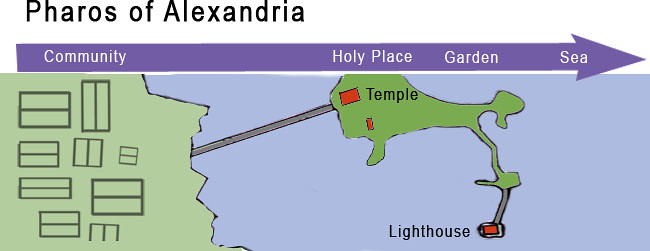

Pharos Island in Egypt has a layout similar to the Taj Mahal, with water separating the community space from the holy space and another water space behind it.

Flowering Walls and Gargoyles

| The cornice dragon makras downspouts are the most obvious features that relate to European cathedrals. These gargoyle-like statues spew water from the roof, though their meaning is quite different than the cathedral beast. They reference Guanyin in a way similar to the mythological phoenix, as a transformation or vehicle of manifestation.

But a closer inspection of the palace reveals other ancient influences. Etched into the walls are flowers, like the flowers, trees, and cherubim that adorned the walls of Solomon’s temple. Dentils poke out of the walls at the ceilings and windows with circular triglyphs above. A sophisticated column order was invented in Himalayan architecture: |

(fairlybuoyant– flickr/creative commons license) |

|

“The ka-ba is a post with lotus-base bre above as transition to the capital. This is divided into four horizontal sections, two with small blocks called bre chung, below the uppermost section that extends out from both sides as scalloplike cloud forms. These are part of the zhu ring or long bow. A narrow beam seat or gdung gdan is interjected to underly the main lintel called the dgung ma. Then follows a band called klu thig in honor of the supernatural naga snakes that are believed to dwell under the ground and in all waters.” j

The row of lotus petals that crown the lintel called padma are like lintels, with stacked blocks above that identified with thunderbolts, exactly like the frieze as explained by Vitrivius.k The sprouting plantlike structure of the ceiling recalls the tracery of medieval vaulted ceilings that represent plants or flames, with a finial at the peak. |

(Party0– flickr/creative commons license) |

“A higher, cantilevered level may be painted with flaming jewel patterns and/or lotus flowers and the auspicious endless knot, while proper rafters above these are often given floral (lotus) designs at the ends. Narrow layers between cantilever beams are called bab skyangs bskums and ceiling planks or gral ma are supported by all that is below.” j

Later Architects Influenced

| Frank Lloyd Wright

A photograph of the Potala Palace hung in the study of Frank Lloyd Wright.l It was inspiration for several of his projects, most notably the Taliesin House in Wisconsin. The blend of stone and red and white structure uses some of the same details, with rows of dentils atop colonnades and grand ascending processions. Tolstoy |

(danobrienmuzyka– flickr/creative commons license) |

Russian author Ilia Tolstoy traveled to Tibet as an ambassador for the Allies in World War II. The Allies sought a pathway through the Himalayas for their troops pass through. Along with Captain Brooke Dolan, Tolstoy extensively documented his travels and excited interest with films and photographs of the Potala Palace.

© Benjamin Blankenbehler 2013

Citations:

[Featured images by:

╬ಠ益ಠ) on flickr/public domain

╬ಠ益ಠ) on flickr/public domain

Originalwana on wikipedia/public domain

Inconnu on wikipedia/public domain

[References:

^ The Evolution of the Indian Stupa Architecture in East Asia, by Eric Stratton, Vedams eBooks (P) Ltd, 2002, p. 129

^ Discoveries in Western Tibet and the Western Himalayas: Essays on History, Literature…, Marialaura Di Mattia, by International Association for Tibetan Studies Seminar, BRILL, 2007, pp.66-67

^ Tibetan arts- Series of basic information of Tibet of China, by Wenbin Xiong, China Intercontinental Press, 2006, p. 42

^ OMFactory, Tibet October 2010(Pt.2):Lhasa and Beyond, by Vrindavan, http://www.omfactorynyc.com/blog/2010/11/lhasa-and-beyond-october-2010/

^ “Tibet- Land of Snows”, by Giuseppe Tucci, as quoted in Himalayan Architecture, by Ronald M. Bernier, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997, p. 78

^ Tibet, by Michael Buckley, Bradt Travel Guides, 2012, p. 155

^ Discoveries in Western Tibet and the Western Himalayas: Essays on History, Literature…, Marialaura Di Mattia, by International Association for Tibetan Studies Seminar, BRILL, 2007, p.66

^ A Portrait of Lost Tibet, by Rosemary Johnes Tung, University of California Press, 1996, pp.19

^ Discoveries in Western Tibet and the Western Himalayas: Essays on History, Literature…, Marialaura Di Mattia, by International Association for Tibetan Studies Seminar, BRILL, 2007, p.65

^ Himalayan Architecture, by Ronald M. Bernier, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997, p. 46

^ see Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture IV, Ch3, v1,6

^ see “Frank Lloyd Wright” by Robert McCarther, 95