| The author of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz, L. Frank Baum, was a Theosophist. The cyclone that brought Dorothy to the land of Oz had a literal and symbolic meaning from his religion.

The founder of Theosophy, Helena Blavatsky, told a real-life tale very similar to the whirlwind that brought Dorothy to Oz. Theosphists told of special people who experienced levitation, whom she called “human magnets.” She described them floating in the air in “rapturous joy, and with eyes overflowing with tears, congratula[ing] each other upon this new manifestation of the mysterious force.” Author L.F. Baum studied these stories. 1 In Russia, a family “descended into the cellar under the house,” just as Aunt Em had escaped from the tornado into the cellar. Then “the whole of the earthenware, cups, tureens and plates, as if snatched from their places by a whirlwind, begin to jump and tremble… the heavy bedstead [was] seen levitating towards the very ceiling.”1 |

a

|

In L. Frank Baum’s book, Dorothy slept in her bed while her house levitated into the sky. Uncle Henry ran to the stables in the story, just like “the terrified girls, who escaped within an inch of their lives by violently shutting and locking the door of the stables.” Dorothy “took a basket and filled it full of bread” inside her house, much like the girl in Russia. “In an instant the basket was filled to the brim.”

These “manifestations… such striking proofs” of levitation were fairly common, and they followed a particular pattern.

“All such phenomena took place not in darness or during night, but in the daytime, and in the full view of the inhabitants of the little hamlet; moreover they were always preceded by an extraordinary noise, as if of a howling wind, a cracking on the walls, and raps in the window-frames and glass.” (H. Blavatsky)1

The experience was frightening, but in the end the cyclone was a blessing. Blavatsky said, “…there is nothing whatever of supernatural in the cases,” and that it had the “least possible evil motive.” This was why Dorothy was unafraid during the house’s levitation: “…she stopped worrying and resolved to wait calmly and see what the future would bring.” (15-16) Dorothy even fell peacefully asleep.

Like the “first-class Spiritistic Star” in Russia who had this experience, she didn’t feel “in the least annoyed.” When the Witch disappeared in a whirlwind Dorothy “was not surprised in the least.” (28) In the film, Dorothy was also a spiritualisc star, labeled “the young lady who fell from a star…”

“Dorothy did not feel nearly as bad as you might think a little girl would who had been suddenly whisked away from her own country and set down in the midst of a strange land.” (33)

Whirling To Progression

“The house whirled around two or three times and rose slowly through the air… The north and south winds met where the house stood, and made it the exact center of the cyclone. In the middle of a cyclone the air is generally still, but the great pressure of the wind on every side of the house raised it up higher and higher, until it was at the very top of the cyclone” (14-15)

Dorothy’s journey was a result of the North and South winds meeting. In Egypt, these forces were symbolized by Hapi and Imsety. Whirling was a common transportation when two forces met in the land of Oz. The good witches of the north and south whirled two or three times to travel: “The Witch gave Dorothy a friendly little nod, whirled around on her left heel three times, and straightway disappeared…” (28)

Dorothy’s journey was a result of the North and South winds meeting. In Egypt, these forces were symbolized by Hapi and Imsety. Whirling was a common transportation when two forces met in the land of Oz. The good witches of the north and south whirled two or three times to travel: “The Witch gave Dorothy a friendly little nod, whirled around on her left heel three times, and straightway disappeared…” (28)

Hoodoo witches would likewise “whirl round on de left heel” as part of the spell of protection: “This whirling-on-the-heel is also a magic rite – of separation, protection, comtempt… it keeps the name (also footspring?) from returning.” 2

Scarecrow whirled when Lion attacked him at their first meeting: “It astonished me to see him whirl around so” (67) He also whirled in the film.

Moses called a great wind to open a path through the waters of the Red Sea. In much the same way, the wind carried Dorothy across the red desert to the land of Oz. It was a whirling of separation, divine protection, and contempt. Dorothy remarked “I can’t go back the way I came.” This was because the wind pushed one direction, toward progress.

Communism and other social movements of Baum’s day often used the theme of upward progression from a spiral or whirlwind. 3

This spiral theme first got its origin from Egypt. Ancient Egyptians believed that the deceased “assumes the powerof the bennu-bird, or the shen-shen, both of which ascend the air to a great height in a spiral whirls. The deceased character prayed that he may ‘wheel round in whirls’ and circle heavenward with the spiral motion of the bennu, i.e., the typical phoenix.” 4

This was the astral body (Ka) leaving the physical body post-death, to be glorified by the sun (Ba), and finally reunited with the physical body when the breathing rituals were completed (Akh, the bird).

“Birds fly over the rainbow; why then, oh why can’t I?” This spiral upward motion occurred at the presence of the new light, the unmanifest logos. It represented the personal manifestation of Dorothy’s logos, but was also the macrocasm of human progression.

“Now every “Round” (on the descending scale) is but a repetition in a more concrete form of the Round which preceded it… On its way upwards on the ascending arc, Evolution spiritualises and etherealises, so to speak, the general nature of all… when the seventh globe is reached (in whatever Round) the nature of everything that is evolving returns to the condition it was in at its starting point— plus, every time, a new and superior degree in the states of consciousness.” (H. Blavatsky)5

The primitive hut evolved into a higher form of spirituality, until Dorothy at last reached the palace of her actualized self. The spiritual forces of the north and south met to raise her toward rebirth.

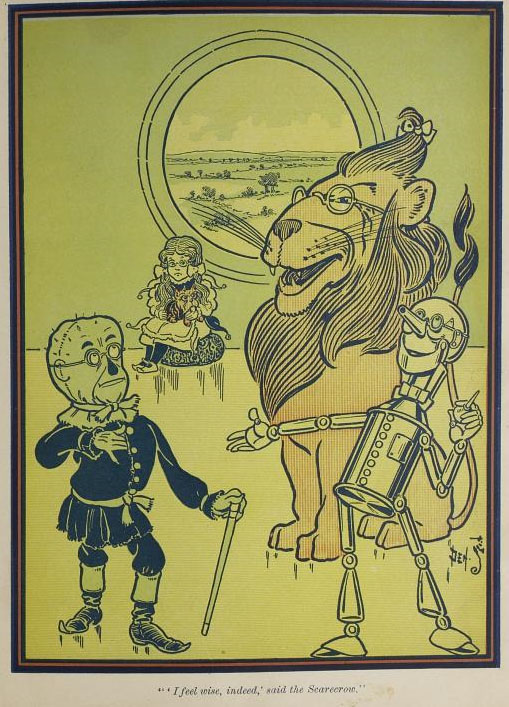

Evolution Of Scarecrow, Timnman, Lion

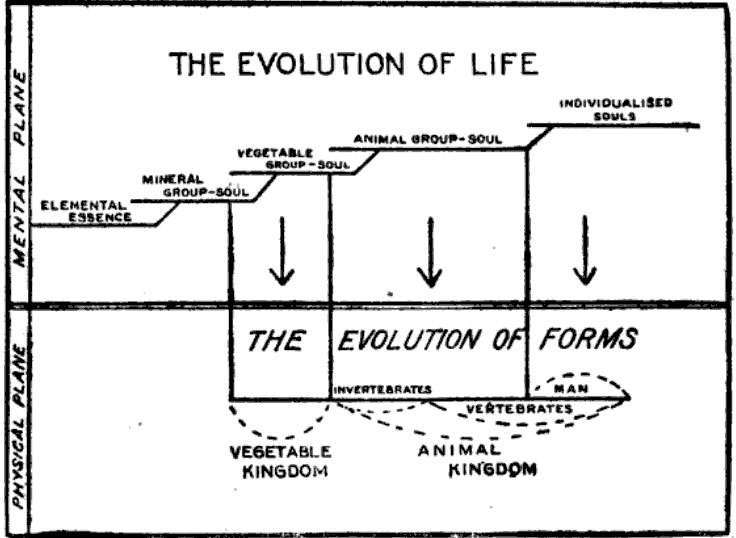

Dorothy’s friends represented the evolution of Dorothy toward rebirth. They represented the three kingdoms of nature in Theosophy which she must pass through. The Tinman was the mineral, Scarecrow was the vegetable, and Lion was the animal:

Dorothy’s friends represented the evolution of Dorothy toward rebirth. They represented the three kingdoms of nature in Theosophy which she must pass through. The Tinman was the mineral, Scarecrow was the vegetable, and Lion was the animal:

“Therefore Nature (in man) must become a compound of Spirit and Matter before he becomes what he is; and the Spirit latent in Matter must be awakened to life and conciousness gradually. The Monad has to pass through its mineral, vegetable, and animal forms, before the Light of the Logos is awakened in the animal man.” (H. Blavatsky)6

Dorothy’s passage in Oz referenced these three categories of universal evolution, and the seven days of creation: “…taking the dog in her arms, [Dorothy] followed the green girl through seven passages and up three flights of stairs until they came to a room at the front of the Palace.” (124)

Each of her three friends sought spiritual attributes that were necessary to navigate the afterlife. Blavatsky taught the necessity of these three virtues along the golden path:

“There is a road, steep and thorny, beset with perils of every kind, but yet a road, and it leads to the very heart of the Universe… There is no danger that dauntless courage cannot conquer; there is no trial that spotless purity cannot pass through; there is no difficulty that strong intellect cannot surmount. For those who win onwards, there is reward past all telling—the power to bless and save humanity…”7

Blavatsky’s order of virtues was the same as in Oz— courage, heart, and brains. Her Hindu source for this Theosophical teaching called it a linear evolution, a particular order. The Hindu teaching of Swami Vivekananda had Four Yogas:

- (Return home)- Royal union or liberation

- (Courage)- Discipline of action

- (Heart)- Loving devotion to a personal God

- (Brain)- Path of knowledge

A person moved up one Yoga to the next. Tinman had a brain but could not feel, and the Lion had a heart and a brain but not courage. Each one was a step forward.

Each considered their missing attribute the key to their enlightenment:

“If you only had brains in your head you would be as good a man as any of them, and a better man than some of them. Brains are the only things worth having in this world, no matter whether one is a crow or a man.” (47)

“I shall take the heart… for brains do not make one happy, and happiness is the best thing in the world.”(61)

“…my life is simply unbearable without a bit of courage… as long as I know myself to be a coward I shall be unhappy.” (70)

“…she decided if she could only get back to Kansas and Aunt Em it did not matter so much whether the Woodman had no brains and the Scarecrow no heart, or each got what he wanted.” (61)

Categories Of Evolution

The four heroes represented the four kingdoms of the world: animal, vegetable, mineral, human.

Each was afraid of a corresponding natural element: fire (Scarecrow), water (Tin man), air (Dorothy), and earth (Lion). When he was cured, “The Lion declared he was afraid of nothing on earth” (203)

The four kingdoms of creation in Egyptian religion mirrored the four cardinal directions of the earth. 12 The Egyptian Book of Gates described how God plotted out the vareities of life.

“Atum (Re in his setting-sun aspect) leans on a staff over four prone figures called the Tired Ones… in all three registers, long processions of deities are engaged in activities connected with measuring, allotting, and apportioning…

Horus addresses a procession of sixteen figures made up of four groups of four. Each group represents one of the four races of mankind as the Egyptians knew them: Men (Egyptians), Asiatics, Negroes, and Libyans….

This concept, offered without the slightest clue to its provocation, finds a measure of corroboration in the works of the twentieth-century Russian mystic and philospher G.I. Gurdjieff.” 13

Four main categories of humans likewise appeared in the Wizard of Oz: Munckins, the people of Oz and Glinda, Winkies, and Flying Monkeys.

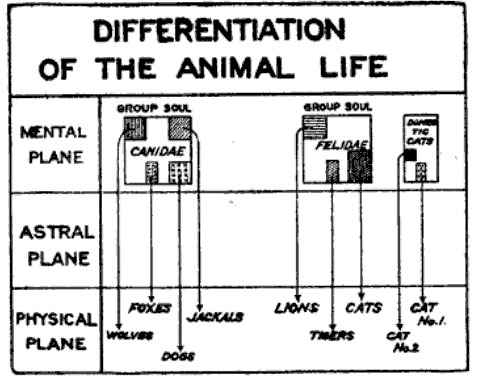

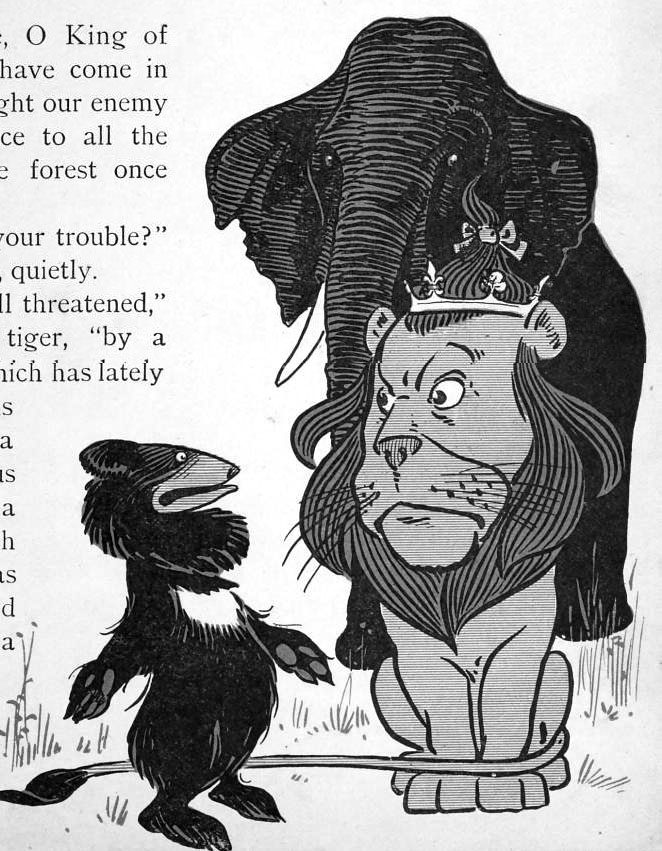

These categories of animals as listed were taken straight from Theosophy’s “differentiation of the animal life.”bLion gathered all the animals of the land, as king of the animals, much like the bibical gathering of animals by Noah. “…were gathered hundreds of beasts of every variety. There were tigers and elephants and bears and wolves and foxes and all the others in the natural history…” (238)

These categories of animals as listed were taken straight from Theosophy’s “differentiation of the animal life.”bLion gathered all the animals of the land, as king of the animals, much like the bibical gathering of animals by Noah. “…were gathered hundreds of beasts of every variety. There were tigers and elephants and bears and wolves and foxes and all the others in the natural history…” (238)

Theosophists categorized the animal kingdom by canines, felines, etc like a tree. The different races and species of life “shot out like the boughs of a tree from the first central group of the four, and shoot out in their turn numberless side groups.” 14

They categorized life into seven categories, from the least to the most evolved.

They categorized life into seven categories, from the least to the most evolved.

“Theosophy recognizes seven kingdoms, because it regards man as separate from the animal kingdom and it takes into account several stages of evolution which are unseen by the physical eye, and gives to them the mediaeval name of “elemental kingdoms.” 15

Blavatsky claimed that this teaching came straight from ancient Egypt.

The same principle applied to the solar system: “’Seven Luminous Ones’ accompany Osiris-Sun” on his journey to rebirth, the seven planets who are also the “seven angels of the Presence.” 16 Galileo’s observation of seven notes in the musical scale and seven colors in the spectrum led to the popular idea that seven was the magical number of creation.

Lion considered himself just another category of animals before becoming King of the Beasts.

“All the other animals in the forest naturally expect me to be brave, for the Lion is everywhere thought to be the King of the Beasts… If the elephants and the tigers and the bears had ever tried to fight me, I should have run myself…” (68)

The film changed this order of beasts which reside in the forest: Lions, Tigers, and Bears.

The film changed this order of beasts which reside in the forest: Lions, Tigers, and Bears.

The book mentioned the horse as a synonym for the Lion. Dorothy thought the Cowardly Lion was “as big as a small horse.” (68) The Witch repeatedly tried to harness him like a horse (147,150,151), and he complained of getting fed porridge which was “food for horses, not lions.” (115) The elephant and horse therefore can be added to the list of beasts.

The book presented these animals in order of largest to smallest, which also was thought to be the order of geographic location from the South to the North: Elephant, Lion, Tiger, Bear, Horse. This particular list of beasts was very significant to ancient Mesopotamia, and trickles down to the racial supremacist teachings of Vitruvius.

Theosophy quoted the ancient Hindu Brahamana to get a similar list.

“Elephants, horses, Sudras [the lowest caste in Hinduism], and despicable barbarians, lions, tigers, and boars are the middling states caused by the quality of darkness.” 17

This Hindu list of beasts came all the way from ancient Egypt:

The symbolism of the Master of Animals is usually understood in the context of a world where people were still competing for resources with animals on a daily basis.

In Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley lions, tigers and bears presented very real threats to small populations that were still reliant on hunting and fishing to subsidize their diets.” 18

A similar list appeared in the ancient Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh: “I killed bear, hyena, lion, panther, tiger, stag, red-stag, and beasts of the wilderness.” 19

Stag in this passage was synonymous with horse, as revealed earlier in the tale: “Oh, Enkidu, whose own mother’s grace was every bit as sweet as any deer’s and whose father raced just as swift and stood as strong as any horse that ever ran.” (Tablet VIII)

“As mythical symbols, the Horse and the Stag both represent the birth of the sun… The Stag is, in many respects, a very similar symbol to the Horse; it too has an age-old association to the sun and fire, and like the horse’s mane the stag’s horns also represent rays of the sunlight.” 20

This reveals that Lion also represented the journey of the sun at Springtime, like the fiery phoenix of the Egyptian resurrection, another kind of whirlwind. Lion was an Egyptian phoenix of courage. The cover illustration of Wizard of Oz portrayed lion as the phoenix, the beast of resurrection.

“The cult of the Lion was also very ancient in Eygpt, and it seems to have been tolerably widespread in early dynastic times; the animal was worshipped on account of his great strength and courage, and was usually associated with the Sun-god, Horus or Ra…” 21

Pain of Opposites

In the ephemeral Theosophic vision of color, the inititate discovered a two-edged sword of sacred truth. Each evolution brought both a blessing and a curse:

“Then he cried out ‘Is there always to be pain!’ and the answer came softly, softly, ‘Yea, until the lesson is learned.’

He wept bitterly but through his tears came a great strength, and by and by he understood.” 8

Knowledge brought both the bitter and the sweet. The spoken Truth “compels the significance of the respective poles, since negativity and posititivity require an underlying concept of opposition/affinity in order to render them meaningful.” 9

Scarecrow received sensibility to discern truth, which gave him pleasure but also pain:

“I don’t mind my legs and arms and body being stuffed, because I cannot get hurt. If anyone treads on my toes or sticks a pin into me, it doesn’t matter, for I can’t feel it. But I do not want people to call me a fool, and if my head stays stuffed with straw instead of with brains, as yours is, how am I ever to know anything?” (39)

The Tinman had once had a heart but lost it, because man can get hurt with the fruit of knowledge. Lost love is painful and disarming. “Hearts will never be practical until they can be made unbreakable.”

Lion’s case of opposition was a specific allusion to Pharoah’s kingship. The Pharoah used imagery of a lion to illustrate his superior rule: “… a lion pouncing upon his prey and destroying it without mercy- an image of ruthless savagery was to become a regular of Hittite power.” 10

“For of old the Land of Hatti with the help of the Sun Goddess of Arinna used to rage against the surrounding lands like a lion.” 11

Pharoah didn’t want to be an oppressor of the weak, just like Lion was wary of offending small animals. Great power can so easily be misused.

Sensibility brings physical pain, love brings bitterness, and power corrupts. As America rose to superpower, each case of increased virtue brought a personal vice and a social fear.

| © Benjamin Blankenbehler 2012

Get “Hidden Symbols In The Wizard Of Oz” Now! See also: |

Sources:

^Theosophy Company, Theosophy, Vol. 6, (Los Angeles, The United Lodge of Theosophists, 1917-1918), 38, 35-42

^Hyatt Harry Middleton, Hoodoo—conjuration—witchcraft—rootwork…, (Washington: Western Pub., 1978), 3245

^see for example August Bebel, Women under socialism, (NY: New York Labor News Press, 1904), iv

^Gerald Massey, Ancient Egypt – The Light of the World… 1, (London: T. Fisher Unwin), 331

^Blatavsky, The Secret Doctrine: Cosmogenesis, 232

^H.P. Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine: Anthopogenesis, vol. 2, (Point Loma: Aryan Theosophical Press., 1888), 42

^H.P. Blavatsky, Boris De Zirkoff, Collected Writings: 1890-1891, (USA: Theosophical Pub. House, 1966)102

^Cavé, “In a Temple,” Theosophy, Vol. 12 issues 1-7, 24

^John Anthony West, Serpent in the sky: the high wisdom of ancient Egypt, (Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House, Quest Books 1993), 69

^Trevor Bryce, The Kindom of the Hittites, (USA: Oxford Univ. Press, 2005), 87

^Bryce, The Kindom of the Hittites, 204

^see Plongeon, Queen M’oo and the Egyptian sphinx, 217

^West, The traveler’s key to ancient Egypt: a guide…, 299-300

^Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine, Vol. 1, 221

^C.W. Leadbeater, A Textbook of Theosophy, (Los Angeles: Theosophical Pub. House, 1918), 10

^H.P. Blavatsky, Psychology of Ancient Egypt, (Paris: Le Lotus, 1888), 56

^Max Muller, The sacred books of the East, vol.25, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1886), 163

^Robert McRoberts, Unlocking The Secrets of Ancient Iconography, www.suite101.com…, (4/12/11)

^Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet X

^Gavin White, Babylonian Star-lore: An illustrated guide…, (Lulu, 2007), 36

^E.A. Wallis Budge, The gods of the Egyptians: or, Studies in Egyptian mythology, vol.2, (London: Methuen & co., 1904) , 359-360

^E.A. Wallis Budge, The gods of the Egyptians: or, Studies in Egyptian mythology, vol.2, (London: Methuen & co., 1904) , 359-360

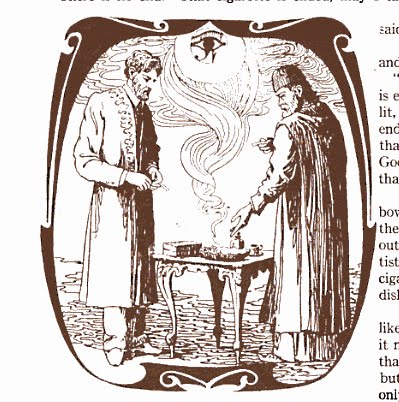

^Image from R. Machell, “Tried in the balance,” The theosophical path, 13 (1918) 413-420 which author L. Frank Baum probably was influenced by.

^Images from: Curuppumullage Jinarajadasa, First Principles of Theosophy, (reprint, Montana: KessingerPub., 1995), 14, 119

All references to and images from the book: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by Lyman Frank Baum, William Morrow and Company, 1900

All references to and quotes from the film: The Wizard of Oz dir. Victor Fleming, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1939