Constant Change

The material world is always changing. There is a part of architecture that is constantly in flux because it reflects the natural environment. But the higher immaterial truths don’t change. The material world is confusing and contradictory, but immaterial truths are enlightening and don’t conflict with each other. Architecture therefore is confusing and contradictory because of the environment it is part of, but the profound truths that it reveals are permanent and unified.

Plato categorized four truths from which people discern their environment. The first two categories of truth rely on observations and predictions of the physical environment. Their sensory data gives them an idea of the material environment. The second two categories lead toward higher immaterial truths.

| Images – Architecture works with images and observations from the environment, and makes it easier to figure out the material world.

For example, the NCMA museum takes the form of common metal barns on an agricultural landscape. The museum visitor may not be well acquainted with agricultural barns and farming, but the form touches upon their basic understanding of what farmland is. |

(Donald Lee Pardue– flickr/creative commons license) |

|

| style=”min-width: 300px;” width=”550″Observations – People have beliefs based on repeated observations of their environment. Architecture manipulates these beliefs.

For example, the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles startles people with a sculptured metal form that is totally different from anything they have seen. The metal texture and building shapes of the city are rearranged and sculpted. People attempt to make sense of this new form. |

(dibaer– flickr/creative commons license) |

|

| Hypothesis – Science and mathematical reasoning in architecture helps people develop fundamental conclusions about their world.

The Pantheon in Rome uses simple proportions, the same proportions used in religious architecture across the world, to relate the cosmic universe to people’s immediate surroundings, and to break everything down to basic mathematical terms. The Pantheon brings together the urban grid, cosmic cycles, human history, religious belief, and daily routine. Mathematic proportions are the universal language of humanity. |

|

Understanding – Complete knowledge is achieved through dialectic. Repeated images and observations of an ever-changing environment along with mathematical reasoning of repeated cycles provide an opportunity for people to consider the opposites of life. Light and darkness, happiness and sadness, good and evil, are all concepts that are understood from dialectic. A complete understanding of cycles and unity in the environment is the highest philosophical knowledge. All truth comes together in unity.

Strategies In Design

| Peter Rowe describes several heuristics that help designers. Each of these strategies should be used to solve the “program” of the project:

Experiential imagining – The architect imagines what it will be like to use or occupy the space. Literal comparison – For example, the form of a building might be derived from a map of cultural populations in the city. |

|

Environmental considerations – Resources available, surrounding conditions, climate, social influences, etc.

Formal Languages – Established languages of design (Classical, Post-Modern, etc.) that would be appropriate for the project program.

Typology – A precedent type of architecture that already exists is used as inspiration. This applies to the building type (house, skyscraper, mall, etc.), the building arrangement (facade, store-front, etc.), and building elements (window, door, etc.).

A building is one piece of a puzzle that makes up people’s beliefs. The first glimpse of a building relates it to what they have observed before. The new Reichstag in Berlin uses the classic dome form to portray a very specific meaning, a new democratic era of government. It takes what people understand about domes and changes it to say something new.

How do all the buildings relate to each other in a city? How do elements relate in a building? Typology helps solve problems in design by answering these questions in several ways.

| Spatial closure – The human mind fills in the missing piece of an object. It uses memory to assume what the whole object is, like block of cheese with a wedge removed. The mind looks for closure and whatever is missing from the whole object says something about the design intent.

For example, the Therme Vals Spa has geometric patches punched out of a large black box. This is a mathematical imposition on natural black stone and suggests a timeless, peaceful logic behind the wonder of nature. |

(felipe camus– flickr/creative commons license) |

Spacial continuation – The human eye fills in the gaps between objects, like a line of dots. The similarity and proximity of objects leads the human brain to connect them in a morphic line. Repeated object thus make up a bigger object or groups of objects. A group of objects relate over time as well. For example, the modern Capitol Building relates to the Pantheon in Paris and the Capitoline Hill before that.

Figure & Ground – The mind uses geometry to figure out the arrangement of objects in space. The golden proportion and certain composition techniques help the viewer understand how distance relate everything.

Reference – Most architecture relates to some previous design, whether vaguely or specifically. This also applies to elements within a design. The mind is constantly referencing the space it is experiencing to other spaces. The program of a kitchen in a house relates more closely to the dining room than it does to the garage.

Archetype – In going through the experiential imagining of design, there are archetypes for people’s experiences. There are certain expectations attached with going to a gas station, for example. You drive up to a pump, pay, pump gas, and leave. This expected experience can be used in designs for similar projects, or can be manipulated for a new kind of gas station. The literal comparisons of a design strategy also might come from formal archetypes.

| Rules – A well-defined schedule of rules might help in typology. Building codes place many demands on a design so that it must fit certain guidelines.

The struggle to get around these rules also plays a part in the form of a building. The WoZoCo Housing in Amsterdam, for example, uses long cantilevers to achieve a large volume even though local ordinances require a small footprint. |

(roryrory– flickr/creative commons license) |

Domains

A designer considers these strategies to achieve a form that serves their needs. The needs of a project are not always quantifiable. For example, the need for a “comfortable space” can be solved in any number of ways and it all comes down to people’s individual opinions of what is comfortable. Everyone’s experience in life is different.

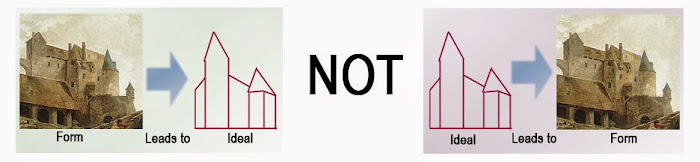

Yet according to Plato there is an ideal form for everything. Many designers make the mistake of trying to start with an ideal form. By definition, ideal truth is immaterial. Ancient architecture considers architecture as an expansion of the ideal form. But you reach an ideal form by perfecting your design, from the bottom up.

First, try to understand the needs for your design. Then, instead of trying to make a perfect form right away, consider how nature derives its forms from trial and error. The flower was perfected over countless iterations of growth and death through the history of the earth. The designer likewise goes through many iterations with many various considerations and solutions. Information unfolds, layer upon layer, as judgments in design become more realistic to build, agreed upon, and appropriate for everybody.

Go through each category of truth as you make your way toward the ideal form: images, observations, reason, and understanding. Only through iteration in design can the imperfect human reach a great ideal form. As the architect runs through all these design strategies, he might want to consider certain aspects of the form in separate iterations. These aspects are called “domains.”

A list of domains might include: Figure, scale, organization, repetition, enclosure, orientation, material, gradation, hierarchy, complexity, balance, proportion, contrast, alignment, anthropomorphism, sustainability, convergence, color.

| In using these domains to achieve strategies of design, carefully consider how much to distinguish each solution.

For example, if a building is going to use both concrete and wood for building materials, how will you relate those materials to each other? For example, the Barclays Center integrates natural green roofs and rusty steel textures in a way that allows each texture to stand out and yet all relate to each other. |

(Reading Tom– flickr/creative commons license) |

Use Of Artistic Mediums

Form and function of unfolds through iterations in different domains, but also through different mediums and different perspectives. The designer traces on floor plans, sites plans, section cuts, elevations, perspective views, detail views, etc. But information is also garnered from physical models and diagrams. Even music, video, collage, poems, and other unconventional artistic mediums give vital opportunity for creative discovery.

The builders of the cathedrals used construction drawings very little. Most of the design came from physical models, trial and error, and widespread collaboration. Research in religious texts, contemplation of philosophy, lengthy trips to the Holy Land, and playful experimentation with building materials all were vital to the creation of the cathedrals. We assume a designer sits in an architect office and draws on a table or computer, but such a method would be extremely limiting.

Computer programs such as CAD are insufficient. Sure, they make it easier to switch between floor plans and other construction drawings. But they still do not adequately switch to other artistic mediums like 3D physical models. As 3D printing progresses, architects will need to use this technology to aid their design processes. CAD programs will need to be able to quickly print models that can be easily manipulated into different shapes and mimic the final building materials.

A wide range of considerations in the design program, such as lighting and security, involve complex calculations that computers can greatly help with.

Evolution & Induction

As technology progresses, tools become increasingly more helpful in the design process. Construction plans in a computer can quickly calculate structural loads and integrate building systems. Design iterations become quicker as computer programs run through a lengthy list of possibilities and throws out the ones that won’t work. Design becomes more automated.

Design becomes more like an evolutionary process. The computer can analyze the design criteria and environmental conditions to find patterns for typology. The computer can unravel the grammar and vocabulary in precedent design. A computer can even analyze the psychological and emotional needs and impacts of certain design possibilities.

But in the end only humans have imagination. Only humans can take the leap toward an invention that has never been done before. This final reminder of the importance of the imaginative designer will help us keep the design human. Don’t get caught up in machine-generated solutions. Keep it human.

© Benjamin Blankenbehler